The suffocating life in the smallest apartment in Latin America

I still haven't decided if it was an incredible anthropological experience or if I will have eternal psychological trauma

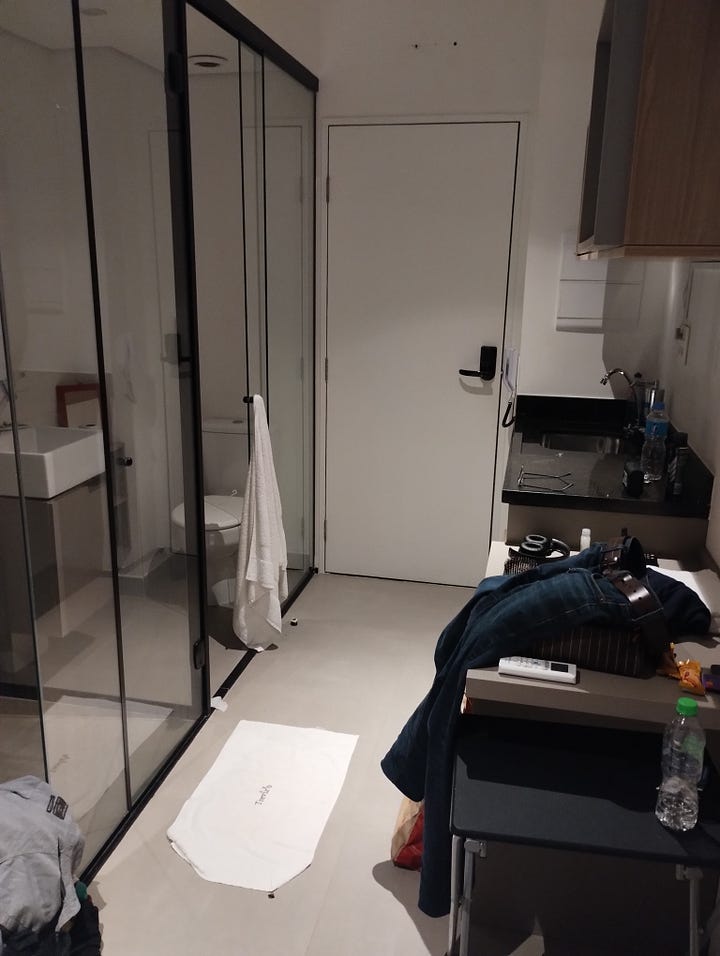

In October, I lived in the "smallest apartment in Latin America”, a slogan the construction company trumpeted at its launch in 2017. I still haven't decided if it was an incredible anthropological experience or if I will have eternal psychological trauma.

The property is in the Santa Cecília neighborhood, in downtown São Paulo. With 10 square meters, I felt like I was in a prison—the one where the Brazilian president Lula was jailed in 2018 and 2019 was 15 square meters.

The place was so small that it caused a visceral anguish, and I couldn't spend much time inside. I used it for fundamental needs, like sleeping and bathing. I spent more money than I should in cafes, restaurants, and wherever possible to be away.

One curious detail is that the bathroom, made of glass, is literally in front of the kitchen. It should have a sign saying "If you need to use the toilet, please don't cook". If it is possible to receive visitors, they should use something other than the bathroom.

"Knowing that the space is limited, we complemented the 10 square meters with shared common areas, which function as an extension of home, as they are full of services for the users", said the Vitacon construction company at the time.

Most of the time I spent in the building's coworking space. It was my salvation to prevent myself from going crazy. However, all the common areas had their problems:

The laundry room had only one washing and drying machine.

The gym had only two treadmills and two bikes.

The coworking space had only two desks.

The "cinebar" was a little market rarely restocked, with a not-so-big television playing Netflix.

I could spend hours complaining about other problems in the building (there were more cockroaches than recommended for a six-year-old building, but I later found out that the neighborhood is going through a crisis of these insects) and the apartment (the shower is the only thing I miss), but I don't want to tire the reader.

The summary is that I felt a strong aversion to the building. I had many reflections during those endless 18 days. What am I doing with my life? How did I end up in this cubicle? Should I stop being a nomad? Should I throw away the money spent and rent a hurriedly and more expensive place to have a better quality of life?

Incredibly, or perhaps suffering from Stockholm syndrome, I learned essential lessons from this experience. The main one is that size took on a different meaning for me. I lived in a 27-square-meter studio for five years and moved out because I couldn't stand such a small space anymore. As I write this text, I am again in a studio apartment of about 30 square meters. I don't even know what to do with this newfound freedom. Everything in life is relative.

I might stay in such a small place again for a very short stay (two or three days). But only if I would spend most of the day outside, sightseeing, or attending an event. I met people who really live in these capsules. The argument from construction companies that this type of property "is made for people who work and study and only come home to sleep" doesn't convince me. What do you do on weekends? What if you want to invite your mother or your girlfriend? Living in something like this is not a life. Not for the price I was paying, which was not cheap.

Finally —and I have written this a few times in this newsletter— nomadic life needs to be planned at least three months in advance so that Airbnb prices and airfares are reasonable. I didn't do that in October in São Paulo, so this mini apartment was the only thing that fit my budget. It was a tremendous mistake.

A friend from Moldova

There was something strange in the behavior of the people in the building. No one greeted each other, and everyone's look was always melancholy. One character, however, caught my attention. A tall guy, 1.80 meters, very pale, very blond, and very hairy, would go out to smoke every half an hour, even in the middle of the night, in an unsafe area.

One day, I was working in the coworking space at dawn when he entered the room a bit desperate and said, in English.

Hey, buddy, can you help me buy a cookie? The transfer went wrong, and I ran out of money tonight. I'm starving. I'll pay you back tomorrow.

We went to the building's internal market. It was the perfect opportunity to find out who this anecdotal human being was.

My name is Vlad, I'm from Moldova, my father does business with Ukraine, our neighbor. But the situation there was getting a bit dangerous because of the war, so I decided to leave. I came to Brazil by chance, and I'm looking for a job. I work with digital systems. I've been in São Paulo for three weeks, and I plan to stay for another two. Thank you very much for the cookie. And you, what's your name, and what are you doing here?

I told him he didn't need to repay me for the one-dollar cookie. Like many people help me in this nomadic life, it's a pleasure to give back—even if this is an invention and he manages to get free cookies every night from a kind soul.

We never spoke again beyond the greetings of "Hey, how are you," but I gained a Moldovan friend and a story to tell even on the darkest days of the suffocating life in the tiny apartment.

What an experience! Well done surviving 18 days in there 😅